BY MATT DAUS

The Central Business District (CBD) Tolling Program is probably the most controversial proposal for reducing traffic and raising funds

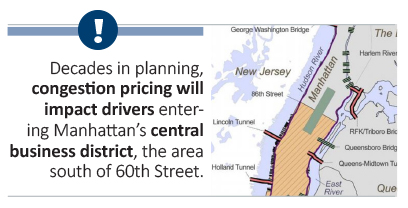

for public transportation in New York City. The variable tolling program will charge motorists that enter or remain in the Manhattan CBD, which is the area south of 60th Street (excluding the FDR Drive and the West Side Highway), and the revenue will be used to fund $15 billion worth of improvements to the public transportation system run by the Metropolitan Transportation Authority (MTA). It’s expected to generate $1 billion per year.

The program required federal approval and environmental review before it could be implemented—a lengthy process that is nearing its end. In June, the Federal Highway Administration issued its Finding of No Significant Impact, which allows the MTA to move forward to determine the final rates and the level of impact on the for-hire vehicle (FHV) industry as well as the public. After last summer’s public comment period, MTA promised that taxis and FHVs would be charged no more than once per day—i.e., the same frequency that regular passenger vehicles will be tolled. Without mitigation measures, it could have done serious harm to the industry.

The program required federal approval and environmental review before it could be implemented—a lengthy process that is nearing its end. In June, the Federal Highway Administration issued its Finding of No Significant Impact, which allows the MTA to move forward to determine the final rates and the level of impact on the for-hire vehicle (FHV) industry as well as the public. After last summer’s public comment period, MTA promised that taxis and FHVs would be charged no more than once per day—i.e., the same frequency that regular passenger vehicles will be tolled. Without mitigation measures, it could have done serious harm to the industry.

The MTA is considering different scenarios that would charge $5 to $23 depending on the time of day (these were the latest proposals as of press time: bit.ly/3JQi6S0). The biggest criticism is that congestion pricing will be in addition to the congestion surcharge that the MTA has been collecting from riders since 2019. These riders have paid the MTA more than $1 billion in taxes on trips south of 96th Street in Manhattan ($2.50 for taxis, $2.75 for FHVs, and $0.75 per pooled ride passenger). The current surcharge is paid by passengers (not drivers), and it applies to taxis, black cars, limos, liveries, and Uber and Lyft vehicles. When combined with the $0.50 MTA taxi surcharge in place since 2009, the MTA has collected nearly $2 billion from taxi and FHV passengers.

Tolling taxi and FHV vehicles once a day raises several questions about logistics, including who will be responsible for the toll. State law requires the fee be passed on to the passenger. However, it seems unfair to put the onus onto the unlucky passenger who happens to be in the vehicle the first time it passes into the CDB tolling zone. Such a scenario could result in some passengers (at least attempting) to shop around for a taxi or Uber/Lyft driver that has already paid the toll for the day.

In June, FHV drivers, in a protest arranged by Independent Drivers Guild (IDG), urged the governor and the MTA to exempt them from what they view as a double tax. IDG is imploring officials to put the congestion toll on passengers, not FHV drivers, to reduce congestion.

Supporters argue that the plan would discourage unnecessary driving, improve air quality, and generate revenue for the MTA. However, there are also politicians on both sides of the aisle—and on both sides of the Hudson—who are fighting it.

Representatives Nicole Malliotakis (R-Staten Island/South Brooklyn) and Josh Gottheimer (D-N.J.) formed the Anti-Congestion Tax Caucus to push for additional study in hopes of slowing or stopping implementation. Representatives Mike Lawler (R-N.Y.) and Tom Kean Jr. (R-N.J.) joined the group, which is using federal legislation, congressional oversight, and the threat of lawsuits to try to stop it.

So far, legislators have introduced the Make Transportation Authorities Accountable and Transparent Act (H.R.159), which would require the Office of the Inspector General to conduct a full audit of the MTA to see how it spent billions in federal assistance, and the Economic Impact of Tolling Act (H.R.1759), which would prohibit the US Department of Transportation from implementing a congestion pricing program for any toll road, bridge, or tunnel until an economic impact analysis is completed and made available to the public.

While N.Y. Governor Kathy Hochul is celebrating the win after clearing federal hurdles, N.J. Governor Phil Murphy has also called out the plan and said that he is “closely assessing all legal options.” N.J. residents already pay to enter Manhattan via the Holland and Lincoln Tunnels; some of the tolling scenarios being floated do take that into consideration.

What’s Next

It is not a question of “if” congestion pricing is coming to New York, but of “when and how much.” The long-sought program is reaching the final stages, and MTA is planning to launch the plan by the second quarter of 2024. The earliest estimates are April 2024. The program is seen as a model for other cities that are struggling with similar issues of urban mobility and sustainability. Once it is established here, we will likely see other cities follow. [CD0723]

Matt Daus is a senior partner at Windels Marx Lane and Mittendorf, and founder/chair of the Transportation Practice Group. He can be reached at mdaus@windelsmarx.com.